Chapter 3 of Mining Massive DataSets #

Motivating the Chapter

We cover the first part of this chapter, which deals with Jaccard similarity, shingling, and minhash.

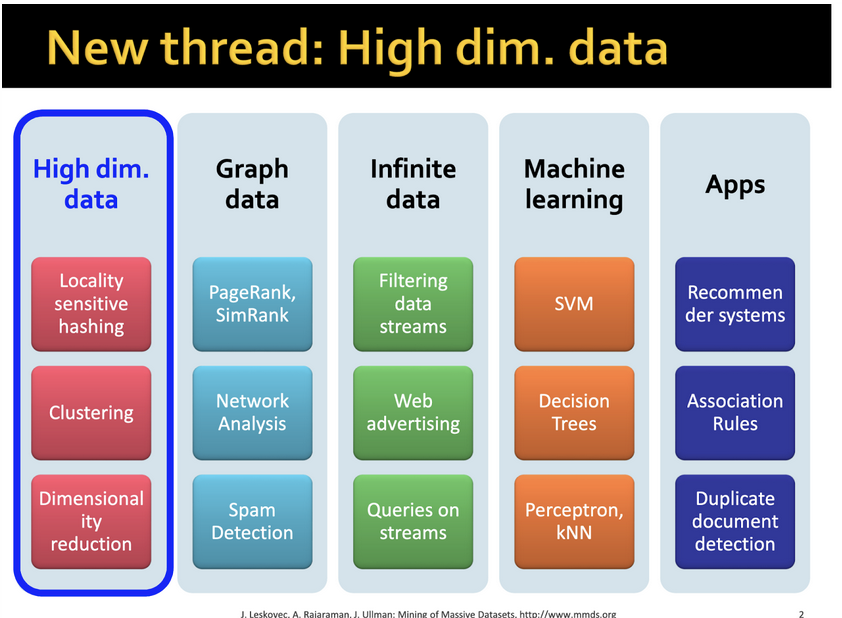

Often these days data analysis involves datasets that have high dimensionality, meaning the data set in question has more features than values and to make statistically sound inferences at scale, require large amounts of data (more info here, on p. 22), and it’s these kinds of datasets that Chapter 3 deals with.

What kinds of datasets have these features? In the world of recommendation systems, most any kind of content we’d like to think about recommending, such as text and images, will be high-dimensional spaces. One important ability in dealing with these types of large datasets is to be able to find similar items, in fact it’s this that underlies the principles of offering recommendations, i.e. how similar is this post to this post, how can we recommend things that are similar to other things we know for sure the user likes?

Before we recommend something, we have to see whether two items are similar. I personally can eyeball whether two paintings are similar to each other, but when you have to compare millions of pairs of items (for example, 10 million posts per day across 500 million blogs), humans don’t scale.

Jaccard Similarity

This chapter of MMDS specifically deals with minhash, one method of combing through millions of items and evaluating how similar they are based on some definition of “distance” between two sets, or groups of items. It was a technique initially used to dedup search results for AltaVista. It can also be used for recommending similar images or detecting plagiarism. It’s mostly used in the context of comparing groups of (text-based) documents. Something that’s important to keep in mind is that we’re not actually looking for the meaning of the sets, just whether these documents are similar on a purely textual level.

The chapter starts out by introducing Jaccard similarity, a metric that we can use to determine whether any given two sets of items are similar, for the mathematical definition of set.

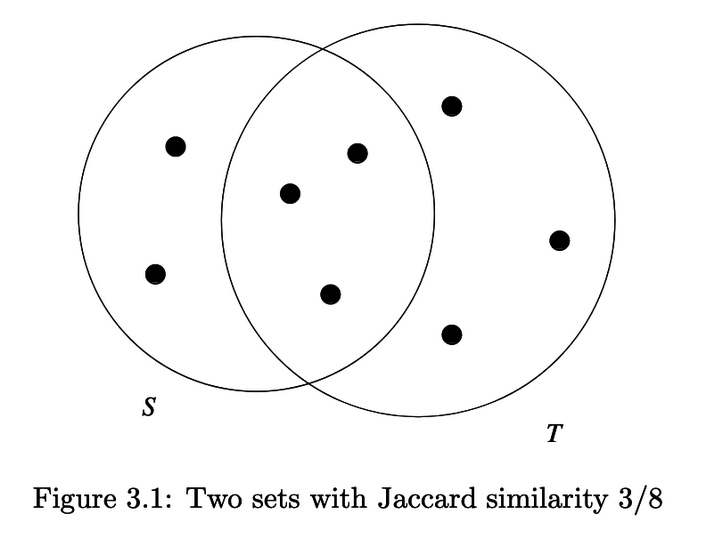

Jaccard similarity is the similarity of sets by looking at the relative size of their intersection divided by their union, or SIM(S,T) = |S ∩ T| / |S U T|. So imagine this is two collections of documents: it could be two web pages and the sentences in their pages, or two directories full of pictures, etc.

Here’s the implementation of Jaccard similarity in Python and Scala.

{{ }}

This is only good for one set of items, though, and doesn’t scale well if the sets are quite large. So we use minhashing, which gets close enough to approximating Jaccard similarity that we can say with confidence that two sets are alike or not alike.

As the minhash paper says,

However, for efficient large scale web indexing it is not necessary to determine the actual resemblance value: it suffices to determine whether newly encountered documents are duplicates or near-duplicates of documents already indexed. In other words, it suffices to determine whether the resemblance is above a certain threshold.

If this sounds familiar to you, it may be because you’re already familiar with datasketches, the family of probabilistic data structures that create quick glances at a large amount of data and tell you with some degree of certainty that items are the same or not the same, or can introspect a set for certain properties. (Bloom filters and HyperLogLog are examples.)

Shingling

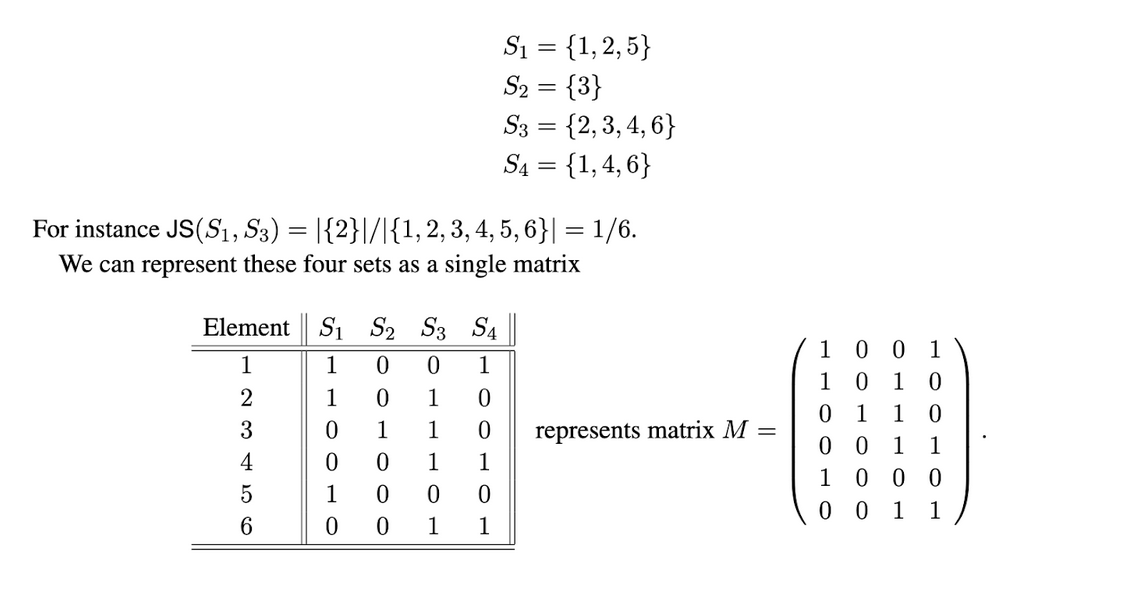

So, in order to compare documents, we need to create sets of them that we can fingerprint and compare the fingerprints to each other. In order to create sets of documents, we create a matrix, where the rows are all of the individual elements in the set that we care about and the columns are any given set.

Here’s a good representation of how this works, from this course. Imagine each set is a single piece of paper with several numbers on it:

For word-based documents, though, we need to get at the letter representations of a set. So, instead of using individual numbers, we use shingles, which are really just short strings of any number of letters.

A document is a string of characters. Define a k-shingle for a document to be

any substring of length k found within the document. So, Suppose our document D is the string abcdabd, and we pick k = 2. Then the set of 2-shingles for D is {ab, bc, cd, da, bd}. If you’ve ever worked with Pig (sorry), you can think of these as bags, or, in most other languages, tuples. So you get a set of tuples.

K can be almost any number we want, but at some point, there will be an optimal number where we don’t get a sparse matrix that’s too large to compute or a matrix that’s too small where the similarity between sets is too high. In this way, picking K is similar to picking K for clustering algorithms where you use the highly scientific method of the elbow method until it looks right.

Minhash

Once we have K, we can set up the matrix. And now we minhash. Here, for example, k is 1.

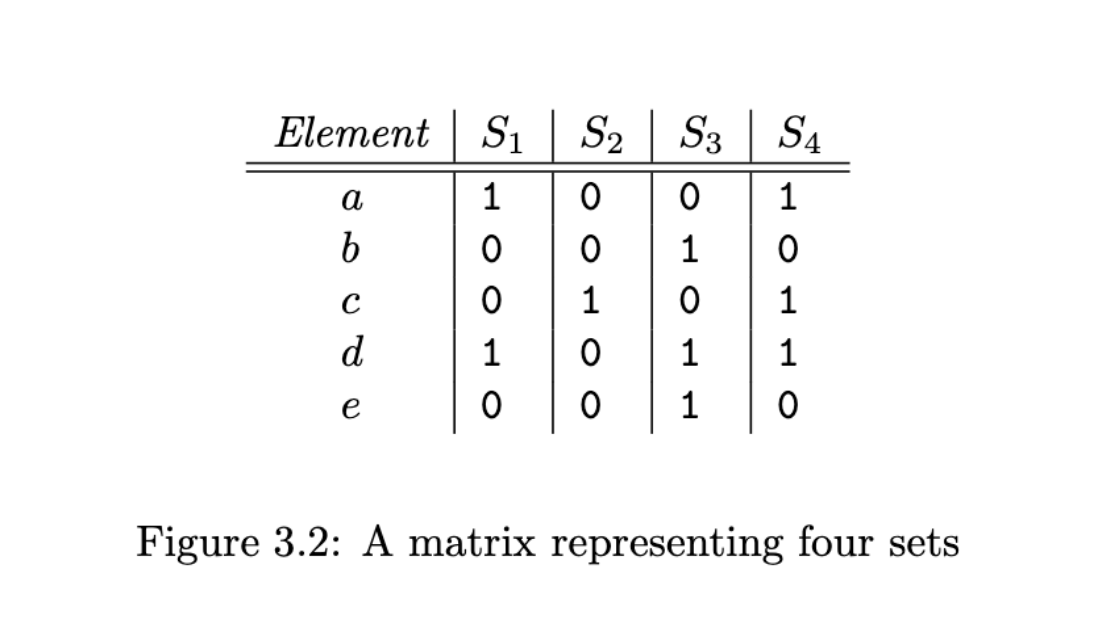

First, we pick a permutation of rows. What this means in English is that we just randomize the letters until they’re in a different order.

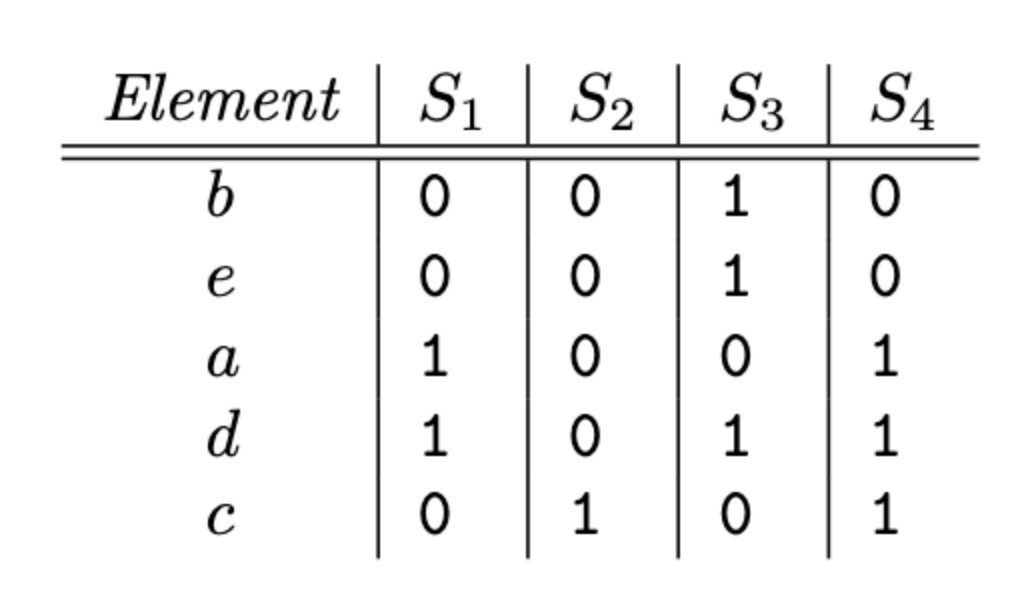

Then, we create the new matrix, indicating whether each letter is in each set in the same position. For example, if we mix up the letters like this, the rows are b,e,a,d,and c instead of alphabetical order.

And we can see, from the first diagram, that for S1, b is 0, so the value of that index is 0, and so on.

Now for the actual minhash function, we keep going down the row until we hit the first 1 value. For S1, that value is a:

column, which is the column for set S1, has 0 in row b, so we proceed to row e the second in the permuted order. There is again a 0 in the column for S1, so we proceed to row a, where we find a 1. Thus. h(S1) = a. And likewise, we see that h(S2) = c, h(S3) = b, and h(S4) = a.

Now we get to the connection between minhash and Jaccard similarity:

The probability that the minhash function for a random permutation of rows produces the same value for two sets equals the Jaccard similarity of those sets

This is really important, because it allows us to use Jaccard similarity as a substitute for manually calculating computations between all the rows/columns of a very large document matrix. And,

Moreover, the more minhashings we use, i.e., the more rows in the signature matrix, the smaller the expected error in the estimate of the Jaccard similarity will be

Here’s a good explanation of how this works with a little more detail than MMDS.

Minhashing Signatures

The problem here is that it will take forever to permutate and calculate the Jaccard similarity between all items and sets. So what we do is create a signature, a fingerprint of each set by using

a random hash function that maps row numbers to as many buckets as there

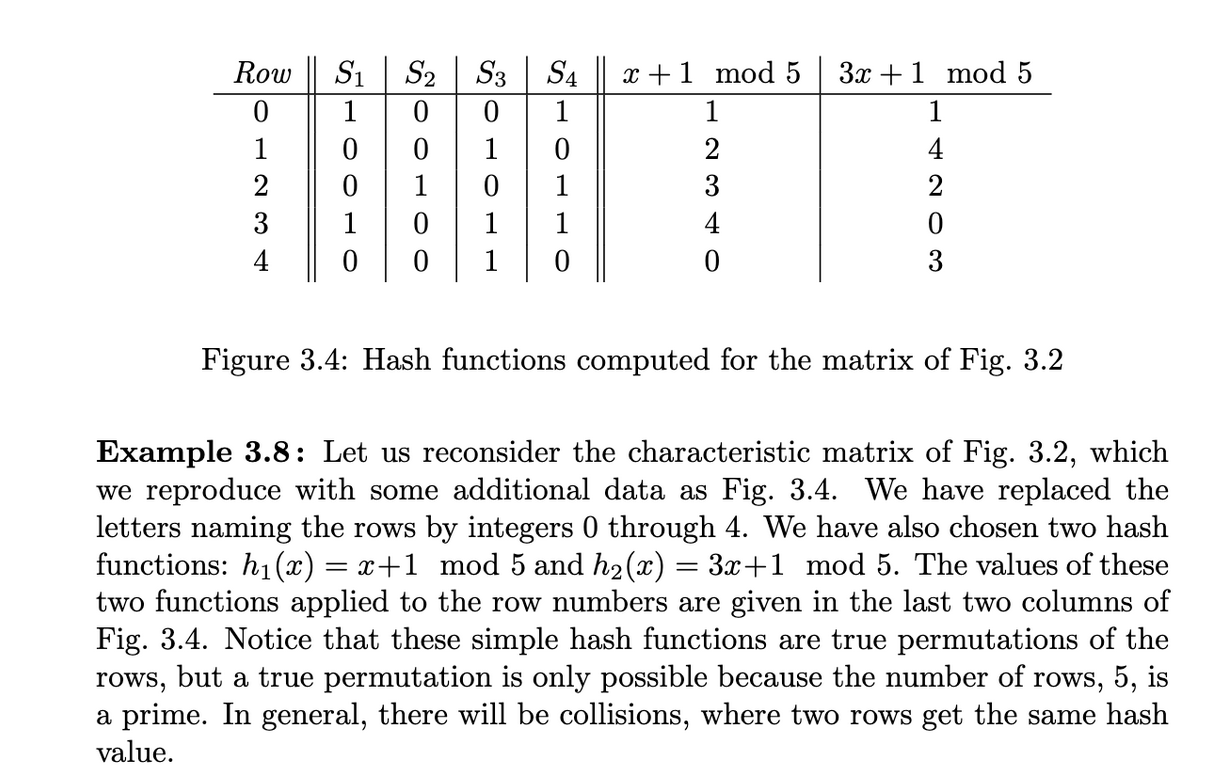

are rows. Thus, instead of picking n random permutations of rows, we pick n randomly chosen hash functions h1, h2, . . . , hn on the rows. We construct the signature matrix by considering each row in their given order, and then we look across the rows.

You can have as many hash functions as you want, but each one will generate a specific number. Get the minimum number of a single hash function, apply across as many as you have, and you’ll get a unique ID for your permutation and then you can compare them across document sets.

MMDS has a good example of this, but I think this is clearer, and this Python implementation is really, really good at explaining what happens in code.